Recently I was asked “When do you choose to catch your drone vs landing your drone?”

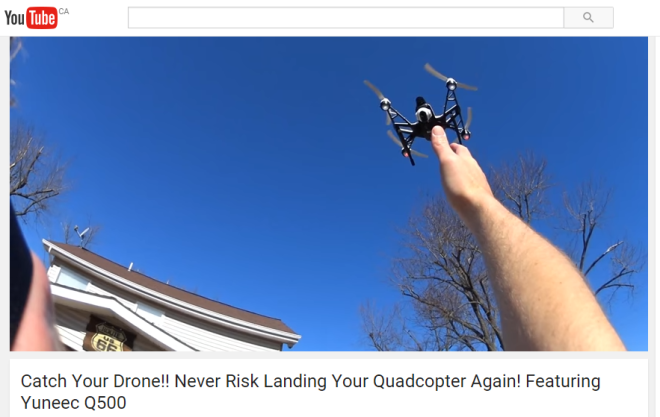

Catching a drone in midflight seems to be a badge of honor amongst some drone pilots and the reasoning behind it is baffling. It’s “so easy to do” there are even videos that teach drone operators how to catch their drone.

They have a number of arguments in favor of doing so.

“I don’t want to risk my UAV hitting the ground.” “Dirt gets into the props when it’s taking off or landing.” “It looks really cool to people watching, and it shows I’m a pro when I catch my drone.”

On Facebook I once made a comment regarding the safety aspect of drone-catching and was promptly rebuffed with “If you can’t catch your drone, you don’t know how to fly” was the leading theme in the long string of derisive commentary that followed. I *can* catch my drone, just as I *can* play tag with an angry bull in a corral (and have done so).

A previous article entitled “Understanding Turbulence,” discusses how rotors and lee-winds can unpredictably affect UAV/drone flight. A human body is an obstacle to wind and the body is capable of diverting rotor wash or create a sink space. While being able to catch a drone mid-flight is certainly ego-supportive, it simply is unsafe for oneself and bystanders.

WARNING, BLOODY IMAGES TO FOLLOW BELOW!

WARNING, BLOODY IMAGES TO FOLLOW BELOW!

OK, YOU’VE BEEN WARNED

Here are a few injuries from around the web, demonstrating a varying degree of injuries by small UAV propellers. Some propellers are nylon-encased plastic. Others are carbon-fiber (CF). CF props are the most dangerous of all as they have no give, and are very sharp on the edges, providing for faster flight and more precise control.

This is a relatively small cut from a prop, incurred while catching a drone mid-flight. An arrogant UAV operator commented “He didn’t know how to fly.” Perhaps the injured person knows how to fly; an unpredictable wind caught his vehicle and caused it to tilt?

A drone selfie and catch went wrong when the props fell into the sinkcreated by a body obstructing air.

Some people simply don’t learn the first time. There are those that count these scars as “badges of honor.” One might call them scarlet letters of stupidity. This person has experience in cutting himself.

With a drone loosely in hand and the motors spinning down,the drone may fall away from or towards the body, catching a bicep or forearm.

This is a similar injury. The injured man was holding his drone by the landing skids and it “pulled away and then towards him” as the quadcopter attempted to self-balance. Nine stitches later, he regretted catching and holding the vehicle. At least the CF blades made for neat and clean slices.

Having a flying Cuisinart at arms-length or less simply isn’t a good idea for a variety of reasons. At arms-length is entirely too close to the face and neck.

A reporter for the Brooklyn Daily was struck by a drone, cutting her nose and chin.

Ultimately, the crew at Mythbusters (they love UAV/Drones and use them in production of their show) did a segment on the potential lethality of drones. Perhaps a bit extreme, one cannot miss their point.

Latin pop-star Enrique Eglasias likely has lost significant sensitivity in his hand due to attempting to catch a UAV during a concert performance. I have little doubt that some UAV operator is reading this blog thinking “That guy is stupid” while justifying why he/she catches their UAV.

I don’t catch my drone because I lack the skill to do so; like most people proficient with a UAV, I can put it precisely where I want it to land.

I don’t catch my drone because I’m averse to injury of myself and others. Safety always precludes “looking cool” or even saving a small cost of operation.

It may look cool to catch a drone and it may even reduce the risk of ingesting dust or dirt particles into a motor, thereby shortening the motor’s life. Perhaps think of it this way; A new motor may cost as much as $50.00. That’s a mere fraction of the cost of a trip to the emergency room and likely significantly less costly than an insurance deductible.

Happy flying!

Douglas Spotted Eagle is an sUAV operator with more than 500 hours of l![]() ogged flight time on various airframe types. He is also a USPA Safety and Training Advisor (at large), and a USPA AFF instructor. Safety is his priority in all aerial endeavors.

ogged flight time on various airframe types. He is also a USPA Safety and Training Advisor (at large), and a USPA AFF instructor. Safety is his priority in all aerial endeavors.