IF A HOMEOWNER DOESN’T OWN THE AIR ABOVE THEIR HOME, WHO DOES?

Recently, heated discussions surrounding the topic of “Air Rights”have arisen within the UAS community, generating confusion and division within the community. In one forum of UAS professionals, an industry member was so angered by the confusion that negative press releases were threatened, jobs were held ransom, and phone calls to local FSDO’s were made.

Recently, heated discussions surrounding the topic of “Air Rights”have arisen within the UAS community, generating confusion and division within the community. In one forum of UAS professionals, an industry member was so angered by the confusion that negative press releases were threatened, jobs were held ransom, and phone calls to local FSDO’s were made.

The intent of this article is to clear up a few misconceptions. Note the author is not an attorney, but rather a very active, long-time member of the aviation and UAS communities (although this article has been vetted by multiple aviation attorneys).

As recently as July 2018, the FAA has re-emphasized their dominion over the National Air Space (NAS), meaning that the citizens of the United States own the NAS, with the FAA being the governing body. Municipalities, cities, and states may not abrogate nor preempt federal control over this airspace.

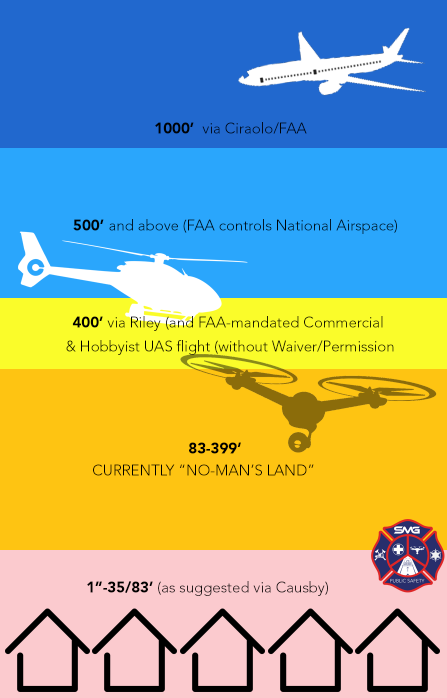

In general terms, once an aircraft is a theoretical “inch above the blades of grass,” it is in the NAS and subject to federal control, not state nor local control.

In general terms, an aircraft at rest/on the ground, may be subject to state or local regulation. Municipalities may control where an aircraft may launch or be recovered through regulation of public grounds. Municipalities should not govern launch/recovery on private property. That said, a few misguided municipalities have created regulation surrounding UAS launch/recovery in much the same way they have mandated that dog houses must meet a certain specification, or that small animals such as chickens may not be raised in certain zones.

We also are observing either blissful ignorance or a coordinated attempt at stifling commercial enterprise in the recent actions of the Uniform Law Commission (ULC), who have proposed national legislation creating “aerial trespass” regulation. These absurd notions have inspired the FAA to release the aforementioned press release regarding their dominion over the skies of CONUS. The National Press Photographers Association offered up a few words to the ULC as well. However, the ULC proposal is just that at this point; a proposal of legislation. It is not law, and unlikely to become such as currently written.

THE REALITY

Taking a specific case in point; a property owner and their real estate agent hire a UAS pilot to capture aerial photos of a home coming onto the market. During the capture of these photos, the pilot’s aircraft is hovering over a neighbor’s home. The camera targets the for-sale home and at no point does the camera capture images of the neighboring home.

Does the neighboring homeowner have a right to demand the aircraft not fly over their home?

No.

So long as the images being captured are of the home the pilot was hired to capture, the neighbor has no claim to control where the UAS flies. Moreover, there is little right to expectation of privacy should the camera capture ancillary areas of the neighbor’s yard (known in legal terms as “curtilage”).

Curtilage “is the area to which extends the intimate activity associated with the ‘sanctity of a man’s home and the privacies of life.’”71 As property owners may “reasonably . . . expect that

[this] area immediately adjacent to the home will remain private,”72 the Court has found that curtilage is protected under the Fourth Amendment. Although the Fourth Amendment’s protections extend to curtilage, the Court has held that property owners do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy against naked-eye observation of curtilage from publicly navigable airspace. (Columbia Journal of Law)Based on existing jurisprudence, warrantless drone surveillance of curtilage may not violate the Fourth Amendment if the drone operates within airspace legally navigable by drones. While this paragraph is predominantly related to law enforcement, it is reasonable to extend the concept into commercial/107 flights.

Homeowners have a right to an expectation of “reasonable privacy.” What is “reasonable” is a matter of debate. Sunbathing in the backyard next door to a home that has a deck higher than a fence, for example, would not be a “reasonable expectation of privacy.”

*it is important to note that the legal term “reasonable expectation of privacy” differs greatly from “right to privacy.”

Unfortunately, there is no Fourth Amendment right to privacy as relates to private citizens or commerce, leaving room for discussion and interpretation. Restrictions which law enforcement must follow in order to observe a property are very different from what a commercial UAS pilot must observe.

It is also a requirement in reading any law regarding privacy that may encompass law enforcement be accompanied by an understanding that law enforcement is held to a higher bar of respecting privacy than a citizen flying a commercial drone. Many states require warrants for any form of aerial surveillance, photography, or videography. Some states require additional certification for public safety officials/first responders, although this issue has recently been seen as a preemption and these requirements may quietly fade away.

IN GENERAL TERMS

The discussion regarding UAS photographing, mapping, or overlying a private home is fairly simple.

Regardless of whether the UAS is flying over a home, yard, easement, or other accessoral structures, a UAS pilot is well within their rights as granted by the FAA (discussion of waivers and airspace aside). So long as there are no MOA, TFR, or similar restrictions in place, the sky is a broadly accessible highway for aerial vehicles.

But…what about the UAS the hovers in a backyard and takes photos of sunbathing children? Doesn’t the FAA regulate this? Doesn’t the homeowner have “air rights?”

No to both questions.

-the FAA doesn’t govern what can/cannot be photographed.

-In theory, the homeowner has no so-called “air rights.” (The concept of “air rights” does exist, but is not related to aviation, rather relating to property views, sunlight blockage, etc, frequently found in large cities such as NYC or LA)

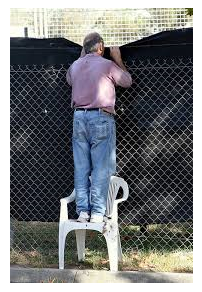

What the homeowner does have, is a potential claim of invasion of privacy. No different than a Peeping Tom putting a ladder on a fence and using the ladder as a photographic elevation, the aircraft’s violation of law is governed by state or local law, not federal law. Privacy laws vary from state to state. For example, in the State of Georgia, taking upskirt photos was legal until late 2017.

Each state has its own definition of “invasion of privacy” and there are no federal laws, and no FAA position on this topic. State laws tend to lean towards anything being under cover, or behind a fence as “private.” However, many state laws do not consider areas over a fence as being “private.” An example might be a two story home with a deck on the upper floor that over looks the neighbors yard. Several precedents have demonstrated that this is an “open view” and not an area that holds an “expectation of privacy.”

In most states, while privacy is a concern, any attempt to regulate “air rights of privacy” would be likely considered preemptive and the FAA has made it clear in recent months they are the controlling agency of aerial operations. The question becomes “at what altitude does the FAA relinquish ownership of the air and the property owner takes possession? Three feet? Ten feet? Eighty three feet? Or is it the theoretical 1” above the blades of grass?

The concept of privacy is not federal; it is local, and no commercial UAS pilot engaged in common, authorized activity such as surveying, mapping, photographing, a client property should hold any concern for this topic at this time. As we evolve from law enforcement situations into privacy situations, it is entirely possible that federal law may change in favor of creating some sort of regulation relevant to aerial invasion of privacy. The FAA has done an exemplary work in providing states with a basic fact sheet that should advise municipalities on what they may/may not regulate with regard to UAS use.

WHAT ABOUT AVIGATION? (air easements)

In the recent spate of social media word battle, one or two individuals brought up their expertise in “avigations.” Avigation is an easement generated for purposes of keeping the peace in areas where aircraft may be landing or taking off. Issues ranging from fuel dispersion, noise abatement, dust/debris, fumes, vibration, etc may impact a homeowner’s quality of life. These issues bear no relevance to UAV operations. Avigations frequently fall under categories of “hazard” and “nuisance.” These sorts of issues frequently precede condemnation actions. Only an airport may possess an avigation easement.

“Control” easements also exist, requiring property owners to restrict the height of buildings, trees, power poles, etc yet again, these easements are of no concern to UAS pilots.

BUT, BUT, BUT…WHAT ABOUT UNITED STATES V CAUSBY?

“Doesn’t that judgement say that property owners own the air up to 83’ above their home? That’s what a lot of websites say…”

Causby’s decision primary does exactly the opposite of what some may feel it controls. Causby demonstrates that airspace is within the public domain, but did NOT determine the quantity of curtilage left to the land owner. Even in the instance that some court somewhere determines that 100% of non-built up property is sacrosanct, Causby provides jurisdiction by the FAA, not state nor local authority. This is likely the most misunderstood of all legal decisions relating to aviation with regards to UAS.

ADDITIONALLY…

It is of significant note to realize that currently, the vast majority of precedent decisions relate to law enforcement use of manned aircraft for purposes of surveillance. As society becomes more aware of issues surrounding privacy, federal legislation may eventually be enacted which restricts FAA control of the NAS. To date, there are three relevant cases to non-law enforcement uses of UAS.

Singer v Newton relates to private use of UAS, and is a District Court decision, affecting only areas within the State of Massachusetts, although it will likely be referred to in many courts to come. City of Chicago v Hakim determined that the local police had failed to meet a burden of proof in arresting a holder of an RPC for “flying over people.” Chicago v Hakim also demonstrates why the FAA must remain the sole arbiter and controlling agency over the skies. Similarly, City of Los Angeles v Chappell determined that Los Angeles municipal laws (MCS 56.31) were a preemption of FAA authority over the skies, although the code is similarly worded to FAA regulations found in Part 107 of the Code of Federal Regulations. In LA v Chappell, Mr. Chappell’s drone had been confiscated and he was charged with violation of municipal ordinances. It’s interesting to note that the last line of the ordinance nullifies the entire ordinance if the aircraft and operator are operating under permissions of the FAA. In other words, a holder of a 107 RPC could not be found in violation unless violating other FAA operational or airspace requirements. The courts found in his favor and his aircraft was returned.

Eventually, complaints will come before the Courts, and we’ll likely see an invocation of some form of legal statement, and perhaps case law, setting a precedent. For now, what we have are listed above. Change, is inevitable.

HOWEVER…

Aside from the legal implications and responsibilities, it is this author’s opinion that UAS pilots have an obligation to the community and each other to raise awareness of activities. Awareness can be raised through common practices such as wearing blaze orange or yellow hazard vests, putting up sandwich boards, marking launch/recovery areas with hazard cones, placing advanced notification handbills on front doors or mailboxes in the area of operations, notifying local authorities of operations, having vehicles marked as a commercial UAS vehicle, having a visual observer in place to communicate with anyone questioning the operation, and more. I believe it is incumbent on the professionals engaged in this infant industry, to help the general public learn to understand and accept our activities and see that it can be professionally practiced, vs the poorly dressed, angry guy that shows up with a small drone, launches from a sidewalk, and screams at the neighborhood about “his right to fly the drone anywhere he damn well pleases.” Being positive, firm, and informational goes a long way to helping concerned individual understand what a pilot is photographing, and allay fears of invasion of privacy.

Angry bystanders, homeowners, or property owners typically become angry due to fear, uncertainty, or doubt (FUD). Generally, they are uninformed. Politely and firmly providing educational information in a calm manner will generally allay their concerns. There will always be “that one person” who won’t accept what they’re being told, and situations may be escalated. Try to keep yourself calm. If authorities are summoned, have your relevant documentation available such as any waivers, RPC, etc. A recording of the altercation may be valuable.

Remember that the municipality *may* have determined authority over launch/recovery areas, so ensure public areas are always used for launch/recovery, or that the landowner has provided (preferably written) permission to launch/recover from their property.

At the end of the day, it is the responsibility of the UAS pilot to be familiar with all local and State regulations regarding UAS flight, and aware of what is and is not permissible. After all, being fully informed is but one facet of being a professional, wouldn’t you agree?

Relevant reading material:

California v. Ciraolo (1986)

Dow Chemical Co. v. United States (1986)

Florida v. Riley (1989)

Los Angeles vs Chappell (2016/Chappell prevailed)

City of Chicago v Hakim (2017/Hakim prevailed)

Singer v Newton (2017/Singer prevailed)

But…what about the UAS the hovers in a backyard and takes photos of sunbathing children? Doesn’t the FAA regulate this? Doesn’t the homeowner have “air rights?”

But…what about the UAS the hovers in a backyard and takes photos of sunbathing children? Doesn’t the FAA regulate this? Doesn’t the homeowner have “air rights?”

Simple answers to questions a lot of people are asking. Great stuff!

Excellent discussion of an important and often misunderstood subject. Thank you!

Very informative . . . thank you !

Great tead and very informative. Shared with our local FB group, Pittsburgh Drone Masters.

Thank you again.

CopterBob

Well written, thanks!